Discover the History

Cyprus the island of Aphrodite

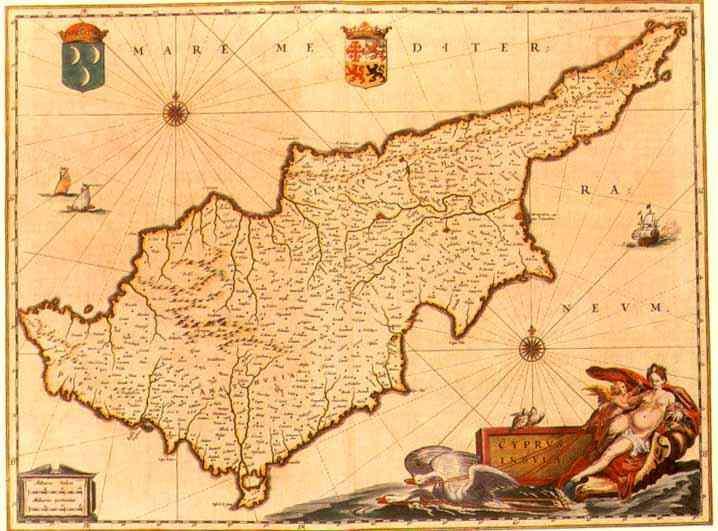

Situated at the crossroads of three continents and the meeting point of great civilizations, Cyprus developed and maintained for thousands of years, its culture, assimilating various effects, remaining, however, Greek cultural center and keeping as far firmly and definitively the Greek character.

![cyprus-political-map-1600[1]](https://panaudit.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/cyprus-political-map-16001.jpg)

Introduction to Cyprus History

The history of Cyprus is one of the oldest recorded in the world. From the earliest times Cyprus´ historical significance far outweighed its small size. Its strategic position at the crossroads of three continents, as well as its considerable supplies of copper and timber combined to make it a highly desirable territorial acquisition.

The first signs of civilization go back to the 9th millennium BC, while the discovery of copper on the island brought wealth and trade to the island. Around 1200 BC a process began that was to stamp the island with an identity that it still has today; the arrival of Mycenaean – Achaean Greeks as permanent settlers, who brought with them their language and culture. Cyprus was subsequently conquered by various nations but, nevertheless, managed to retain its Greek identity, language and culture intact.

The Turkish Cypriots came much later. They were descendants of the Ottoman Turks who occupied the island for more than 300 years between the 16th and 19th century, and have contributed their own heritage to the country.

Christianity was introduced to the island during the 1st century AD by St. Paul himself and St. Barnabas, founder of the Church of Cyprus.

Brief Historical Survey of Cyprus

Neolithic Period (8200-3900 BC) – Remains of the oldest known settlements in Cyprus date from this period. They can best be seen at Choirokoitia, just off the Nicosia to Limassol highway. At first, only stone vessels were used. Pottery appeared on a second phase after 5000 BC.

Chalcolithic Age (3900-2500 BC) – Transitional period between the Stone Age and the Bronze Age. Most Chalcolithic settlements were found in western Cyprus, where a fertility cult developed. Copper was beginning to be discovered and exploited on a small scale.

Bronze Age (2500-1050 BC) – Copper was more extensively exploited bringing wealth to Cyprus. Trade developed with the Near East, Egypt and the Aegean, where Cyprus was known under the name of Alasia. After 1400 BC Mycenaeans from Greece first came to the island as merchants. Around 1200 BC, mass waves of Achaean Greeks came to settle on the island spreading the Greek language, religion and customs. They gradually took control over Cyprus and established the first city-kingdoms of Pafos, Salamis, Kition and Kourion. The hellenisation of the island was then in progress.

Geometric Period (1050-750 BC) – Cyprus was then a Greek island with ten city-kingdoms. The cult of the Goddess Aphrodite flourished at her birthplace Cyprus. Phoenicians settled at Kition in the 9th century BC. The 8th century BC was a period of great prosperity.

Archaic and Classical Period (750-310 BC) – The period of prosperity continued, but the island fell prey to several conquerors. Cypriot Kingdoms became successively tributary to Assyria, Egypt and Persia. King Evagoras of Salamis (who ruled from 411-374 BC) unified Cyprus and made the island one of the leading political and cultural centers of the Greek world. The city-kingdoms of Cyprus welcomed Alexander the Great, King of Macedonia, and Cyprus became part of his empire.

Hellenistic Period (310-30 BC) – After the rivalries for succession between Alexander’s generals, Cyprus eventually came under the Hellenistic state of the Ptolemies of Egypt and belonged from then onwards to the Greek Alexandrine world. The Ptolemies abolished the city-kingdoms and unified Cyprus. Pafos became the capital.

Roman Period (30 BC – 330 AD) – Cyprus came under the dominion of the Roman Empire. During the missionary journey of Saints Paul and Barnabas, the Proconsul Sergius Paulus was converted to Christianity and Cyprus became the first country to be governed by a Christian. Destructive earthquakes occurred during the 1st century BC and the 1st century AD and cities were rebuilt. In 313 the Edict of Milan granted freedom of worship to Christians and Cypriot bishops attended the Council of Nicosia in 325.

Byzantine Period (330 – 1191 AD) – After the division of the Roman Empire, Cyprus came under the eastern Roman Empire, known as Byzantium, with Constantinople as its capital. Christianity became the official religion. New earthquakes during the 4th century AD completely destroyed the main cities. New cities arose, Constantia became capital and large basilicas were built from the 4th to 5th century AD. In 488 Emperor Zeno granted the Church of Cyprus full autonomy and gave the Archbishop the privileges of holding a scepter instead of a pastoral staff, wearing a purple mantle and signing in red ink. In 647 Arabs invaded the island .For three centuries Cyprus had been constantly under attack by Arabs and pirates until 965, when Emperor Nicephoros Phocas expelled Arabs from Asia Minor and Cyprus.

Richard the Lion Heart and the Knights Templar (1191 – 1192) – Isaac Comnenus, a Byzantine governor and self proclaimed ‘Emperor’ of Cyprus, behaved discourteously to survivors of a shipwreck involving ships of King Richard’s fleet on their way to the Third Crusade, including Richard’s sister Joanna, Queen of Sicily, and his betrothed Berengaria of Navarre. Richard in revenge defeated Isaac and took possession of Cyprus marrying Berengaria of Navarre in Limassol where she was crowned Queen of England. A year later he sold the island for 100.000 dinars to the Knights Templar, a Frankish military order, who resold it at the same price to Guy de Lusignan, deposed King of Jerusalem.

Frankish (Lusignan) Period (1192 – 1489) – Cyprus was ruled on the feudal system and the Catholic Church officially replaced the Greek Orthodox, which though under severe suppression managed to survive. The city of Famagusta (Ammochostos) was then one of the richest in the Near East. It was during this period that the historical names of Lefkosia, Ammochostos and Lemesos were changed to Nicosia, Famagusta and Limassol, respectively. The Frankish rule was brutal and oppressive. The era of the Lusignan dynasty ended when the last Queen Catherine Cornaro ceded Cyprus to Venice in 1489.

Venetian Period (1489 – 1571) – Venetians viewed Cyprus as a last bastion against the Ottomans in the east Mediterranean and fortified the island, tearing down lovely buildings in Nicosia to reduce the boundaries of the city within fortified walls. They also built impressive walls around Famagusta, which were considered at the time as works of art of military architecture.

Ottoman Occupation (1571 – 1878) – In 1570 Ottoman troops attacked Cyprus, captured Nicosia, slaughtered 20.000 of the population and laid siege to Famagusta for a year. After a brave defense by Venetian commander Marc Antonio Bragadin, Famagusta fell to the Ottoman commander Lala Mustafa who at first allowed the besieged a peaceful exodus, but later ordered the flaying of Bragadin and put all others to death. On annexation to the Ottoman Empire, Lala Mustafa Pasha became the first Governor. The Ottoman Turks, whose descendants are today’s Turkish Cypriots, were to rule Cyprus until 1878. The Muslim minority during the Ottoman period eventually acquired a Cypriot identity. Initially, the Greek Orthodox Church was granted a certain amount of autonomy, the feudal system was abolished and the freed serfs were allowed to acquire land, though heavily taxed. As the power of the Ottoman Turks declined, their rule became brutal and corrupt and there were many instances when Greek and Turkish Cypriots alike struggled together against the oppression of Ottoman Rule. It was with a certain amount of optimism – sadly misplaced – that Cyprus would be united with Greece that British rule was welcomed.

British Rule (1878 – 1960) – Under the 1878 Cyprus Convention, the Ottoman Turks handed over the administration of the island to Britain in exchange for guarantees that Britain would protect the crumbling Ottoman Empire against possible Russian aggression. It remained formally part of the Ottoman Empire until the latter entered the First World War on the side of Germany, and Britain in consequence annexed Cyprus in 1914. In 1923 under the Treaty of Lausanne, Turkey relinquished all rights to Cyprus. In 1925 Cyprus was declared a Crown colony. In 1940 Cypriot volunteers served in the British Armed Forces throughout the Second World War.

Hopes for self-determination being granted to other countries in the post-war period were shattered by the British who considered the island vitally strategic, especially after the debacle of Suez. If the island became part of Greece, Britain would lose its bases and influence in the area. Applying a policy of divide and rule, Britain rekindled Turkey’s ambitions for Cyprus. Ankara could not countenance a Greek island so close to its soft underbelly. Britain used the Turkish Cypriots, who formed 18% of the population, as weapons in their fight against the Greek Cypriots and deliberately involved Turkey, which began to advance the idea of partition.

The Cyprus problem has its roots in foreign interference and occupation. For centuries, Cyprus has been occupied by one power or another but through it all has kept intact its predominantly Hellenic nature and Christian Orthodox traditions. The ambition of enosis, or union with Greece, was already strong when Greece won its own independence from the Ottomans in the 19th century. When Britain became the ruling power in Cyprus, the hope that this dream could become reality became even more intense. After all means of peaceful settling of the problem had been exhausted, a national liberation struggle was launched in 1955 against colonial rule and for union with Greece.

The liberation struggle ended in 1959 with the Zurich-London agreements signed by Britain, Greece and Turkey as well as representatives of the Greek and Turkish Cypriots, leading to Cyprus´ independence

———————————————————————————————————————-

Hopes for self-determination being granted to other countries in the post-war period were shattered by the British who considered the island vitally strategic, especially after the debacle of Suez. If the island became part of Greece, Britain would lose its bases and influence in the area. Applying a policy of divide and rule, Britain rekindled Turkey’s ambitions for Cyprus. Ankara could not countenance a Greek island so close to its soft underbelly. Britain used the Turkish Cypriots, who formed 18% of the population, as weapons in their fight against the Greek Cypriots and deliberately involved Turkey, which began to advance the idea of partition.

The Cyprus problem has its roots in foreign interference and occupation. For centuries, Cyprus has been occupied by one power or another but through it all has kept intact its predominantly Hellenic nature and Christian Orthodox traditions. The ambition of enosis, or union with Greece, was already strong when Greece won its own independence from the Ottomans in the 19th century. When Britain became the ruling power in Cyprus, the hope that this dream could become reality became even more intense. After all means of peaceful settling of the problem had been exhausted, a national liberation struggle was launched in 1955 against colonial rule and for union with Greece.

The liberation struggle ended in 1959 with the Zurich-London agreements signed by Britain, Greece and Turkey as well as representatives of the Greek and Turkish Cypriots, leading to Cyprus´ independence.

Republic of Cyprus 1960

According to the Zurich-London agreements, Cyprus became an independent republic on 16 August 1960. As an independent country it became a member of the United Nations, the Council of Europe, the Commonwealth and the Non-Aligned Movement. According to the above treaty, Britain retained two sovereign bases (158.5 sq. km) on the island, at Dekeleia and Akrotiri-Episkopi.

The Zurich – London agreements comprised the Treaty of Establishment, the Treaty of Guarantee and the Treaty of Alliance. Under the Treaty of Guarantee, Britain, Greece and Turkey pledged to ensure the independence, territorial integrity of Cyprus as well as respect for its Constitution. The Treaty of Alliance between Cyprus, Greece and Turkey was a military alliance agreed for defense purposes. These agreements also became the basis for the 1960 Constitution.

The 1960 Constitution incorporated a system of entrenched minority rights unparalleled in any other country. The 18% Turkish Cypriot community was offered cultural and religious autonomy and a privileged position in the state institutions of Cyprus (Turkish Cypriot Vice President, three out of the ten Ministers of the Government and 15 out of 50 seats in the House of Representatives). The Turkish Cypriot leadership’s use of its extensive powers of veto gave rise to deadlock and inertia. In November 1963, when Cyprus´ first President Makarios put forward proposals for amendment of the Constitution in order to facilitate the smooth functioning of government, the Turkish side promptly rejected them, arguing that the Constitution could not be amended without the entire independence agreement being revoked.

The Turkish Cypriot ministers withdrew from the Council of Ministers and Turkish Cypriot civil servants ceased attending their offices. The ensuing constitutional deadlock gave rise to intercommunal clashes and Turkish threats to invade. Since then, and despite the fact that normality gradually returned to the island, the aim of the Turkish Cypriot leadership, acting on instructions from the Turkish Government, has been the partitioning of Cyprus and its annexation to Turkey.

Turkish Invasion and Cyprus Occupation

On 15 July 1974 the ruling military junta of Greece staged a coup to overthrow the democratically elected Government of Cyprus.

On 20 July Turkey, using the coup as a pretext, invaded Cyprus, purportedly to restore constitutional order. Instead, it seized 35% of the territory of Cyprus in the north, an act universally condemned as a gross infringement of international law and the UN Charter. Turkey, only 75 km away, had repeatedly claimed, for decades before the invasion and frequently afterwards, that Cyprus was of vital strategic importance to it. Ankara has defied a host of UN resolutions demanding the withdrawal of its occupation troops from the island.

On 1 November 1974, the UN General Assembly unanimously adopted Resolution 3212, the first of many resolutions calling for respect for the sovereignty, independence, territorial integrity and non-alignment of the Republic of Cyprus and for the speedy withdrawal of all foreign troops.

Furthermore, the General Assembly, the Security Council and the Commission on Human Rights of the United Nations as well as the Non-Aligned Movement, the Commonwealth, the European Parliament, the Council of Europe and other international organizations have demanded the urgent return of the refugees to their homes in safety and the full restoration of all the human rights of the population of Cyprus.

The invasion and occupation has had disastrous consequences. About 142.000 Greek Cypriots living in the north – nearly one quarter of the population of Cyprus – were forcibly expelled from the occupied northern part of the island where they constituted 80% of the population. These people are still deprived of the right to return to their homes and properties. A further 20.000 Greek Cypriots enslaved in the occupied area were gradually forced through intimidation and denial of their basic human rights to abandon their homes. Today there are fewer than 600 enslaved persons (Greek Cypriots and Maronites).

The invasion also had a disastrous impact on the Cyprus economy because 30% of the economically active population became unemployed and because of the loss of:

• 70% of the gross output

• 65% of the tourist accommodation capacity and 87% of hotel beds under construction

• 83% of the general cargo handling at Famagusta port

• 40% of school buildings

• 56% of mining and quarrying output

• 41% of livestock production

• 8% of agricultural exports

• 46% of industrial production

• 20% of the state forests

Furthermore, Turkish forces occupied an area which accounted for 46% of crop production and much higher percentages of citrus fruit production (79%), cereals (68%), tobacco (100%), carobs (86%) and green fodder (65%).

About 1.500 Greek Cypriot civilians and soldiers disappeared during and after the invasion. Many had been arrested and some were seen in prisons in Turkey and Cyprus before their disappearance. The fate of all but a handful remains unknown. To resolve this humanitarian issue it is essential to have Turkey’s cooperation.

Turkey has also promoted the demographic change of the occupied territory through the implantation of Anatolian settlers. Since the invasion some 115.000 Turks from Turkey have been illegally imported in the occupied area. This large influx of settlers has negatively affected the living conditions of the Turkish Cypriots. Poverty and unemployment has forced over 55.000 to emigrate and they now make up only 11% of the native population.

35.000 Turkish soldiers equipped with the latest weapons and supported by the Turkish air force and navy, are still in the occupied area making it, according to the UN Secretary-General’s Report (December 1995), ‘one of the most densely militarized areas in the world’.

The illegal regime in the occupied area has pursued a deliberate policy aimed at destroying and plundering the ancient cultural and historical heritage of the island, as part of a wider goal to ‘Turkify’ the island and erases all evidence of its Cypriot character. Abundant evidence gathered from foreign and Turkish Cypriot press, as well as evidence obtained from other authoritative sources (Jacques Deli bard’s UNESCO report); demonstrate the magnitude of the damage and destruction caused to the cultural heritage of Cyprus.

As a consequence of Turkey’s policy and illegal actions:

• at least 55 churches have been converted into mosques

• another 50 churches and monasteries have been converted into stables, stores, hostels, museums, or have been demolished

• the cemeteries of at least 25 villages have been desecrated and destroyed

• innumerable icons, religious artifacts and all kinds of archaeological treasures have been stolen and smuggled abroad

• illegal excavations and smuggling of antiquities is openly taking place all the time with the involvement of the occupying forces

• all Greek place names contrary to all historical and cultural reason were converted into Turkish ones.

In this respect, the Republic of Cyprus is making great efforts to recover stolen items which include invaluable icons, frescoes, mosaics, texts and artifacts. A successful case of repatriation involved the 6th century mosaics that were illegally removed from the church of Panayia Kanakaria in the occupied areas and sold to an art dealer in the USA. Following a legal battle that generated world attention, the US Courts ruled that the mosaics should be returned to their legal owner, the Church of Cyprus. Similar legal battles are now under way in the Federal Republic of Germany, where Cyprus is striving to repatriate hundreds of items stolen from churches in the occupied part of Cyprus.

In contrast to the total disrespect shown by the occupation regime, all Muslim sites in the area controlled by the Government of Cyprus are properly and respectfully kept, preserved and maintained by the competent authorities.

On 15 November 1983 the Turkish-occupied area was unilaterally declared an independent “state”. The international community, through UN Security Council Resolutions 541 of 1983 and 550 of 1984, condemned this unilateral declaration by the Turkish Cypriot regime, declared it both illegal and invalid, and called for its immediate revocation. To this day, no country in the world except Turkey has recognized this spurious entity. Negotiations for the solution of the Cyprus problem have been going on intermittently since 1975 under the auspices of the United Nations. The basis for the solution of the Cyprus problem are the UN Security Council resolutions and two high-level agreements concluded between the Greek Cypriot and the Turkish Cypriot leaders in 1977 and 1979.

In an effort to enhance the prospects for a settlement and safeguard the security of all Cypriots, the Government of Cyprus had formally proposed the total demilitarization of Cyprus. The proposal envisaged the withdrawal of the 35,000 Turkish occupying forces and the disbanding of the Cyprus National Guard and the “Turkish Cypriot Armed Forces” who would hand their weapons and military equipment to UN Peace-Keeping Force (UNFICYP). UNFICYP would have the right of inspection to ascertain compliance with these measures. Turkey refused to consider the proposal and continues to maintain its illegal military hold on the island.

Source: Press And Information Office, Republic Of Cyprus.